TODO: FIX FOOTNOTES

Alt title: Space opera for liberals

Note

- Contains minor spoilers for the first third of the book.

- I’m using the word “liberal(s)” in the political philosophy sense (pro-individual rights, civil liberties, democracy, and free enterprise), not the colloquial American one (synonymous with “progressive”).

I finally got around to reading (most of) The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet (TLWTASAP henceforth), which my favorite brother and sister-in-law have been recommending to me for the last year-and-a-half. I’m embarrassed to admit that when I first spotted the book among the assorted table decorations and party favors at their wedding reception last August, I made the ur-mistake of judging it by its cover.

To me, both the title (kitschy) and cover design (I don’t like it) screamed “off-brand Douglas Adams”, which is a sub-genre of science fiction that’s burned me before [you come at the king, you best not miss]. But my first impression couldn’t have been more wrong, because unlike The Hitchhiker’s Guide and its sequels, Becky Chambers’ debut novel does not contain one iota of irony, nor even much humor at all. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever read in the genre of space opera (which is not entirely a compliment, as you’ll see.)

The book follows the crew of a spaceship named The Wayfarer. They are interstellar highway engineers, contracted by the Galactic Commons to punch holes in the fabric of spacetime so that other ships can get around a bit faster. The GC is a powerful interspecies alliance (think European Union but in space), which recently incorporated humans into its galaxy-spanning bureaucracy. So far, so Mass Effect. The thing about this book that makes me feel slightly insane while reading it is that despite

- taking place on a spaceship

- crewed partially by aliens

- whose job is making wormholes

- in space,

TLWTASAP doesn’t read much like science fiction at all.

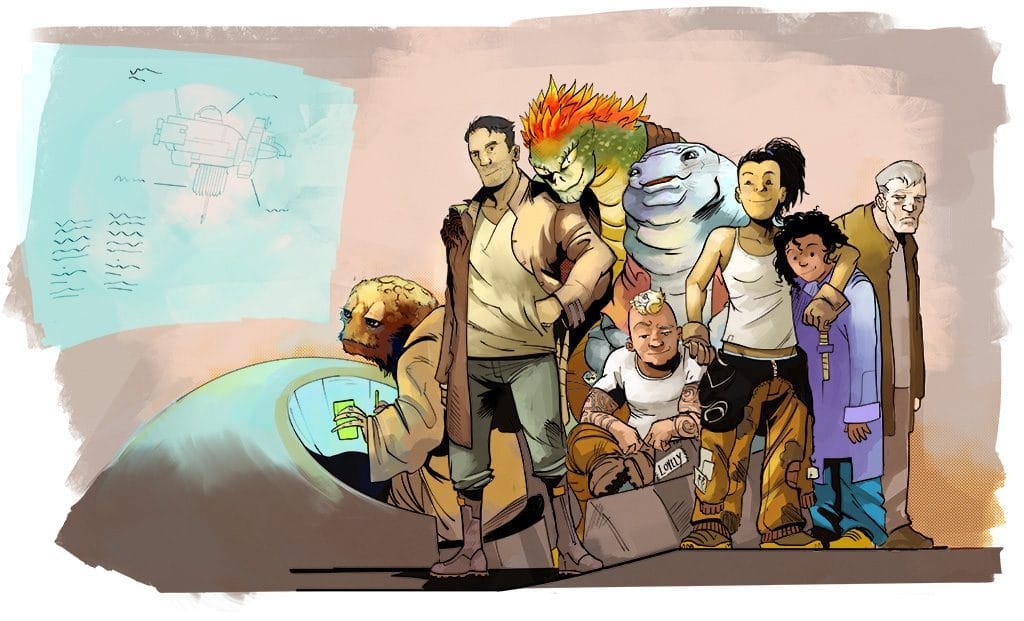

[One thing I can say wholeheartedly in favor of this book is that its unique and friendly characters have inspired some fantastic fan-art. For example:]

Science fiction is sometimes called “the literature of ideas” by its adherents (of which I am one), and this is perhaps the best way to distinguish it from fantasy1 or normie-fiction2. However well rounded the characters or detailed the setting of a sci-fi story may be (or not3), they are almost always employed (and often abused) in service of the exploration of one or more Big Ideas. For example:

-

What if the people living on the moon staged a libertarian revolution? (The Moon is a Harsh Mistress)

-

What if a sudden widespread mutation reversed the physical power imbalance between men and women? (The Power)

-

What would it feel like if you were the brain of a gender-blind spaceship, who can simultaneously inhabit multiple human bodies? (Ancillary Justice)

-

What if spiders were like, smart and stuff? (Children of Memory4)

The central ideas in TLWTASAP feel small by comparison—at least in the first half, it’s largely concerned with things like found family, social practices surrounding gender presentation (using the correct pronouns, etc.), toothless anti-colonialism, and the virtues of nonviolence (except in self-defense). All extremely important concepts, and any of them could be the seed of a great or challenging story idea. Only they are never explored as ideas, but rather presented rather straightforwardly as values5. The book doesn’t ask the interesting questions (what responsibility do Space-EU member species have to the victims of their past colonial empires? Is it time for Space-Reparations?), but instead just gives you the answers (colonialism is bad). Its heart is in the right place, but it typifies a worldview in which bad things only happen because of so-called Bad People—bigots, manipulators, assholes6—rather than the perverse incentives that perpetuate systems of oppression.

Just ten years after it was published, the themes of TLWTASAP feel a bit quaint. They’re table stakes for American liberals (like myself, and doubtless most of you reading), which we no longer need or bother to argue about with our friends (though perhaps our parents could still use coaching now and then). Granted that was much less true back in 2014, when gay marriage wasn’t even federally yet, but in 2024 the book feels bizarrely contemporary for a sci-fi novel. Take the average moral philosophy of attendees at this week’s Democratic National Convention, transpose it onto a multi-species spaceship crew, and you’ve got a good sense of the ideological center of this novel. Human social structures (families, businesses, governments) are indistinguishable from those in the present, and seemingly no progress has been made on any political or economic issues (inequality, exploitation, immigration, etc.) in the centuries (!!) since they abandoned earth and discovered the greater galactic community. It’s all still consumers and capitalists backed by soldiers with guns.

So if the book is about values rather than ideas, and is politically concerned with individual (stop Bad People) rather than systemic (fix Bad Systems) solutions, surely there must be some Bad People that need stopping, right? Well, so far, no. There’s actually almost no conflict whatsoever for the first one or two hundred pages [I’m reading via audiobook, so idk exactly how many], not with any external threats to the ship, nor even between crew members7. When people do eventually start waving guns around, the crisis is diffused through multicultural understanding and nonviolent communication rather than bullets or plasma. The reason, of course, is that the guns-wavers weren’t actually Bad People, just misunderstood; they were themselves victims of the real Bad People, who are somewhere far off camera. The Bad People are always off camera, it seems, which is a shame because it means we’re never allowed to contend with the reasons why the Bad People did the Bad Things in the first place. We’re expected to just write them off as “assholes.”

—SebasP

—SebasP

If it sounds like I’m being overly negative or cynical, I’m not trying to be—I’m really enjoying the book, and have every intention of finishing it. Despite the part-alien cast, it’s deeply humane and unashamedly hopeful. The author plainly believes that people can change for the better, and that everyone deserves to live in peace, with full autonomy of body and spirit—and so do I! But the book’s simplistic “don’t be an asshole” messaging and its overly familiar vision of the future have left me a bit cold.

I’ve been consuming sci-fi books, games, films, and TV voraciously for 20 years or so, and I’ve never seen the aesthetics of space opera used to tell this kind of story, one that’s meant to comfort the reader and affirm their beliefs instead of challenging them8. Now I’m thinking that maybe there’s a good reason for that. Space sucks! It wants to kill you so bad! It’s mind-meltingly big but almost entirely cold and empty. It contradicts our natural desire to make meaning, punching holes in our hubris to think that we could possibly make an impact on all that bigness and coldness. Setting your story in space but then imbuing it with the affective cozyness of a Christmas morning feels like a waste of a perfectly good vacuum.

—

— —

— —

—