We know how this ends. You’re going to die and so will everyone you love. And then there will be heat death. All the change in the universe will cease, the stars will die, and there’ll be nothing left of anything but infinite, dead, freezing void. Human life, in all its noise and hubris, will be rendered meaningless for eternity.

But that’s not how we live our lives. Humans might be in unique possession of the knowledge that our existence is essentially meaningless, but we carry on as if in ignorance of it. We beetle away happily, into our minutes, hours and days, with the fact of the void hovering over us.

— Will Storr, The Science of Storytelling

I step into my usual coffee shop to order a cappuccino, which for some reason (I dare not ask) is what they call an eight ounce latte on most menus in NYC. My temples are aching, but only for lack of sleep and caffeine, as I’m still blissfully unaware of the pulverizing disappointment that’s racing towards me.

The walk was frigid, but in here it’s tropically warm, so I shed my coat, scarf, gloves, and hat into a messy pile before taking a seat at the last remaining table. The cafe is packed like a Christmas market, interior decorated to match, the walls and bar festooned with lights, wreaths, and stockings, a ten-foot pine dominating the center of the room.

Patrons are rooted at their tables in a dense thicket, jackets and bags forming a sparse underbrush. At the end of nearly every pair of arms and hands is a laptop—I count 26 in all—altars of dull black plastic or anodized aluminum where we worship intently, barring the occasional glances we steal at our neighbors’ screens, in case their gods are more interesting than ours. What’s that slide deck he’s working on—“Harnessing Humor for Brand Loyalty?” Gross. Is she drawing furry porn on her iPad? In public? Respect.

A notification chirps onto my screen, wrenching my attention back to my inbox. I scan the new message, and the subject line is enough for me to guess that it bears the news I’ve been dreading all week: “Following up on your interviews.” Guts twisting, I read on:

Hi Mo,

Thank you for taking the time to connect with the team and spend time interviewing with us at [company]. On a personal note, it was a pleasure speaking with you and learning more about your background. I feel fortunate that we had the chance to connect.

We’ve been lucky to have quite a few applicants for the roles on our team. After careful consideration with my hiring team, unfortunately, we won’t be advancing you through to the offer stage. I’m sorry that this isn’t the news that you were hoping to hear and it’s really hard to share it with you.

For the space of a few breaths I feel utterly despondent. My ears burn hot and my headache sharpens, a railroad spike of fresh stress lancing into my grey matter. My mind runs in circles, competing with itself to draw the worst possible conclusion: You’ll never find a job. You’ll never succeed at anything. Everyone hates you. You’re going to die in a gutter, impoverished and alone. And other such self-defeating drivel.

And then, so suddenly I don’t realize it’s happening, my train of thought derails, switching from down to uptown track without any conscious effort on my part. My brain starts writing a very different story, one that goes something like this:

Man, that sucks. But you know what? It’s not really your fault. The job market is fucked right now. And that was your first time seriously interviewing for a job in like seven years, so it’s natural you were a bit rusty. And maybe it’s not so terrible that you didn’t get this job—that company is fully remote, and you’ve gotten sick of working remotely after the last four years.

It’s actually kind of lucky that you got rejected, because otherwise you’d feel pressured to accept the offer just so you could stop looking. Plus you’ve learned a lot in this process, which you can use when it’s time to interview for a job you actually care about. So if you think about it, it really all worked out for the best!

How much of this story do I actually believe? Maybe a third. It does, after all, contain a several grains of truth (nice job, brain). But deep down I know it’s a fiction, a post-hoc rationalization my subconscious has thrown together at the last minute, so I can feel better about failing to get something that I undeniably wanted.

Human beings are incredibly adept at fabricating stories like this to explain away our disappointments. We narrativize our failures and rejections into “plot points” in our heroic arc—an arc which, we can thereby assure ourselves, must surely curve upward over the long run. These stories mostly fall into one (or both) of the following categories:

Story 1: It’s not your fault

It was out of your control. You did your best. There was nothing you could’ve done better, or differently, so there’s no point in getting upset about it, or in changing your behavior next time around.

Lost your job? It definitely had nothing to do with your performance; they were just doing random layoffs. Your dentist says you have twelve cavities? You probably just have bad tooth genetics. (But maybe you should start flossing all the same.)

This nice thing about this story is that it’s often true, more or less. Nearly everything that happens to us isn’t a result of the conscious choices we’ve made, and a great deal of who we are, and even what we do stems from the accidental circumstances of our birth—genetics, family, nationality, the epoch in which we were born. What little control we do have is on the margins: the jobs we pursue, the partner we marry, the hobbies we explore. Even the most agentic individuals rarely do anything more extraordinary than start a business or move to a new country. That isn’t to diminish those accomplishments, just to say that they are choices made within a tightly controlled set of circumstances, prescribed by the dominant culture and economic system. Even our dreams are largely prescribed—why, for example, is starting a business such as popular goal in the first place? Why not dream of becoming a knight, or a feudal lord?

But the danger with telling ourselves we have no control is that we may start using this as an excuse even in the marginal cases where it’s not true, forgiving ourselves from stressful work of changing our beliefs or reevaluating our actions. It’s why I’m skeptical of the watered-down Stoicism found in the Christian Serenity Prayer:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

How can we know in advance which things we can or cannot change, unless we’ve already tried our absolute hardest to change them? It turns out that having “the wisdom to know the difference” is fairly a tall order, and it’s all too easy to simply declare, in advance of trying, that everything is beyond our control, forgiving ourselves for doing and changing absolutely nothing.

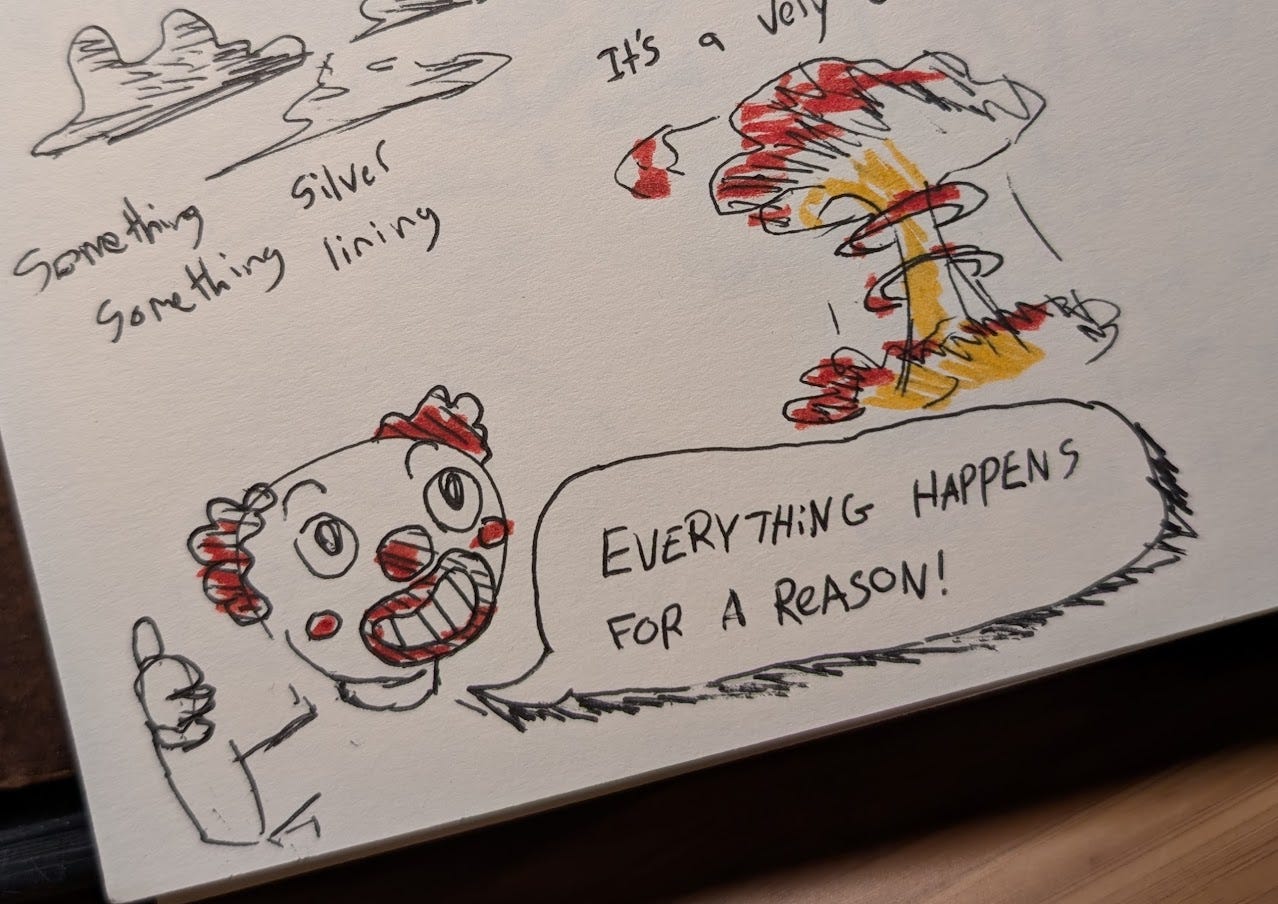

Story 2: It’s for the best

Everything happens for a reason, and the reason is that you are special. God, Fate, or The Universe is looking out for you, and so if something seemingly-bad happens, it must actually be a blessing in disguise, because you’re the hero of this story, and your eventual triumph is inevitable.

Your partner dumped you? You dodged a bullet; clearly they weren’t The One. Injured? Remember, what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Unlike the first story, this one rarely has much truth to it. It’s impossible to know whether anything that happens is actually “for the best”, and that some other chain of events wouldn’t have lead to a happier outcome.

Take my rejected job application—who could possibly say definitively whether this was “for the best”? I might have been incredibly happy working at [company], or unspeakably miserable. Maybe getting rejected saved my life, because I was fated to get hit by a bus on my way to orientation. Or maybe NOW I’m going to get hit by a bus, and I would have been spared if only I was working from home. Ahhh!

One of the great frustrations of being alive is that we can’t see beyond the cresting wave of the present moment. We don’t get to know how things might have been, if we made a different choices.1 We only know how they are—and even that we have a blurry sense of things. So rather than mourn our failures forever, it’s easier to edit the story after the fact, telling ourselves that we’d be even worse off if things had gone otherwise. Which isn’t to say that it’s impossible to employ reason to guess at what might have been, just that we’re often quick to brush our troubles under the rug, declaring “it’s all for the best,” even when there isn’t much evidence to support that conclusion.

Storytelling is perhaps our greatest superpower as a species. Some anthropologists2 hypothesize that it’s our love of narrative that allowed us to expand beyond the limits of family or tribe, using shared stories like religion, ethnicity, and nationality to bind us into ever-larger networks of relations. Under the auspices of these fictions, we can build larger, more complex, and more terrible things than our proto-human ancestors could have imagined—suspension bridges, quantum computers, and cruise missiles, all made possible by the countless overlapping hallucinations that channel our efforts. They also facilitate the disconcerting concentrations of power we witness, today and throughout history, as individuals or oligarchies dictate the stories of an entire city, nation, or empire.

But on an individual level, stories are how we keep ourselves sane. In our minds, we are the hero or victim in an epic we’re reciting for an audience of one—and even when we’re the victim, we’re usually just a temporarily embarrassed hero.

Just like the yarn I spun about my rejected job application, these stories usually stem from a kernel of truth. But as Will Storr writes in The Science of Storytelling, we’ll usually ignore the facts if and when they threaten our sense of personal heroism:

If we’re psychologically healthy, our brain makes us feel as if we’re the moral heroes at the centre of the unfolding plots of our lives. Any ‘facts’ it comes across tend to be subordinate to that story. If these ‘facts’ flatter our heroic sense of ourselves, we’re likely to credulously accept them, no matter how smart we think we are. If they don’t, our minds will tend to find some crafty way of rejecting them.”

It takes constant effort to remind ourselves that the stories we invent unconsciously, about why we fail (it’s not our fault) and what it means (it’s for the best), are really just rationalizations, lies we tell ourselves to feel better, or “cope,” to use the colloquial invective.3

But if they are lies, they may sometimes be useful, even necessary lies. For there are a great many things in life that must be coped with, and many far worse than a missed job opportunity. Heartbreak, injury, betrayal, discrimination, poverty, and death—we use story to transform the rocks of our hardship into stepping stones on our personal hero’s journey. Thus transfigured, we can find the strength to stride across them, lest we be shattered and sunk.

I’m not trying to disabuse anyone of their internal sense of heroism—least of all myself. We should cherish our fabricated meanings, which help us bounce back quickly from setbacks, throwing ourselves once again into the messy work of living well. If we stay alert, not allowing our internal monologue to lure us into complacency or harmful delusion, it might even be possible to live up to our own self-aggrandizing narratives—to actually be heroes.

Footnotes

-

Ted Chiang investigates the antithesis of this—i.e. what if you could peer into an alternate universe where you made a different choice—in his short story Anxiety is the Dizziness of Freedom, in which he convincingly argues that it’s probably for the best that we don’t have access to this information. ↩

-

See: “Seeds of Civilization” and “Cooperation and the evolution of hunter-gatherer storytelling”. ↩

-

And the smarter you are, the better you probably are at lying to yourself. ↩