Alt title: Stop exploiting yourself

Part 1: Help Wanted

“A committee is coming in early next week to evaluate the state of the store, see how we’re doing. They’re also going to decide who to put in place as store manager. But here’s the thing. They want to talk to you guys individually, to hear what you think. They want to make sure that you’re all behind their choice. After all, it’s your store too.”

Big Will flashed a meaningful grin, as he usually did after uttering a platitude.

He asked if anyone had any questions. Nicole eyed the coffeepot—which by now was hissing and sputtering wildly, like a small animal trying to scare off a larger predator—while the people who always asked questions, the ones who thought not having a question would be a humiliating acknowledgement of their own cosmic insignificance and eventual nonexistence, raised their hands.

—Adelle Waldman, Help Wanted

Adelle Waldman’s debut novel, The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., was an instant favorite of mine when I picked it in college. The detailed psychological portrait of the title character, a 30-year old writer living in Brooklyn named Nate Piven, felt like a cautionary tale written just for me. Nate is outwardly self assured and brilliant, but inwardly cowardly, feckless, and self-destructive. Through his interactions with others—particularly women—the author meticulously flays a certain insidious archetype of postfeminist modern masculinity. Nate is avoidant, uncommunicative, and deeply selfish, but never to such a degree that it would endanger his social status. Wiped clean of all visible markers of toxicity, the man that Nate typifies can break hearts with impunity.

To me, on the cusp of entering my twenties, the book was hilarious, depressing, and inspiring all at once; it was a call to action to be a better man than Nate himself. I no longer recommend Nathaniel P. to other people, though, because everyone who’s ever borrowed my copy has found the main character, and consequently the whole book, to be too infuriating to enjoy. From this I gather that many people are not interested in reading books with unsympathetic protagonists.

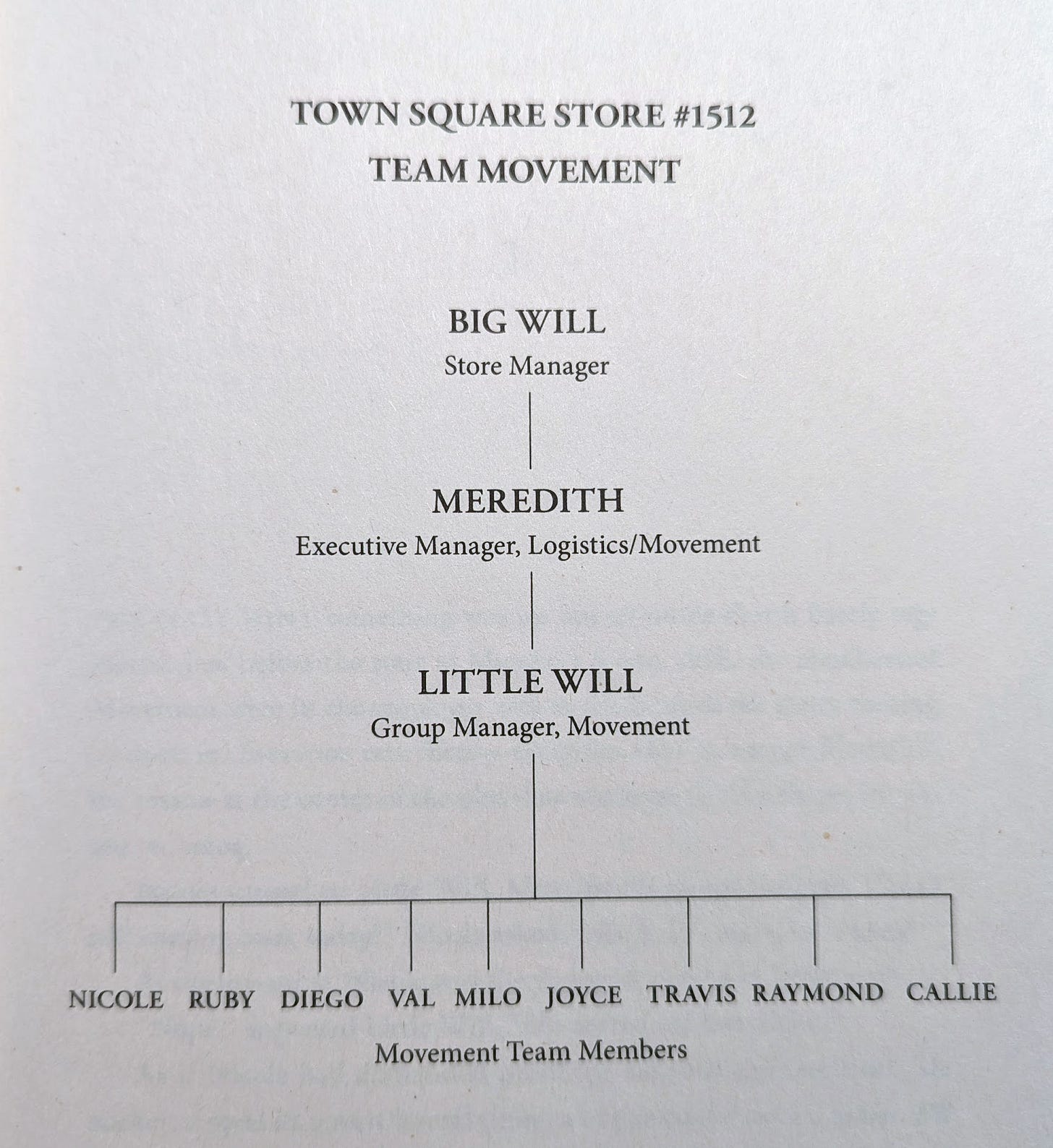

Protagonistically picky readers may have an easier time with Waldman’s second novel, Help Wanted. It’s a “darkly comedic” story about the lives of modern low-wage workers, and it features not one, but twelve main characters (of varying levels of likability). It opens with an org chart depicting the corporate hierarchy of the cast:

The book takes place at “Town Square Store #1512”, a branch of a fictional big-box store in the same vein as Walmart, Target, and Kmart [RIP]. Except for the store manager “Big Will”, the characters above comprise “Team Movement”, which is responsible for unloading trucks of merchandise and restocking the store before it opens. No character’s perspective is especially emphasized or given extra weight over any other; instead, we bounce continually between individuals on the org chart, learning the unique psychological and economic challenges that each of them face. The author’s roving eye never lacks for empathy — she efficiently humanizes each of them in turn, and I was delighted to see how the strengths and flaws of each were interpreted by their peers, and to be able to contrast that with their conception of themselves.

The constantly shifting perspective was also, for me, its primary point of failure. Unlike in The Love Affairs, we never sit for very long in one character’s head, so our impression of each is shallow by comparison. By the time I finished reading Help Wanted**,** I was rooting for almost everyone on Team Movement, but I was left empty of the deeper insights I’d found in Waldman’s first book. I remember reading The Love Affairs at 19 and feeling flabbergasted that anyone could create such a detailed portrait of a mind that was not their own. For all its breadth of cultural critique, Help Wanted didn’t leave me with any particular sense of wonder.

Still, I can forgive Waldman for going broad-but-shallow this time around, because Help Wanted is at least as much an economic critique as a cultural one. Everyone on Team Movement has a unique relationship to money and capitalism. Are they salaried, or paid by the hour? Do they own a car, or walk to work along the freeway? Do they rent an apartment with their spouse, or live rent-free with their mom? The financial details of the characters’ lives complicate how we view their actions. For example Diego has a history of adultery, but I felt much more sympathy for him than I ever did for Nate Piven. Diego is trying to get a car loan, so he can drive to a better-paying second job, so he can move his family out of their basement apartment. Infidelity feels inconsequential next to the harrowing labor of making ends meet. Nate, by contrast, should “know better” than to behave how he does — even if his only real crime was being a mediocre boyfriend.

Given the economic dimensions of Help Wanted, it was a happy coincidence that I was reading another book last week that critiques this unique economic moment from a totally different angle.

Part 2: The Burnout Society

In The Burnout Society, Korean-born German philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues that modern life is characterized by “excess of positivity”. By this, he means that we live in a society that thinks “nothing is impossible”, and so we living in it demand more and more of ourselves over time, reaching for unbounded heights of achievement. He calls us the “achievement-subjects,” who, unlike the slaves and serfs of prior “disciplinary societies”, are suffering under the yolk of “compulsive freedom”, leading us to accelerate our pace of production in a flywheel of “auto-exploitation.” Han says “it leads to a society of work in which the master himself has become a laboring slave. In this society of compulsion, everyone carries a work camp inside.” He believes that the rise of the achievement-subject from the ashes of disciplinary society is the cause of the recent rise in rates of depression, burnout, and chronic fatigue:

Prohibitions, commandments, and the law are replaced by projects, initiatives, and motivation. Disciplinary society is still governed by no. Its negativity produces madmen and criminals. In contrast, achievement society creates depressives and losers.

All of this is great from the perspective of capital. The achievement-subject is a competitive market unto itself; “it succumbs to the destructive compulsion to outdo itself over and over, to jump over its own shadow.” The achiever is far more productive than the laborer of disciplinary societies, who might work only as hard as necessary to avoid reprisals. “Auto-exploitation is significantly more efficient and brings much greater returns […] because the feeling of freedom attends it.”

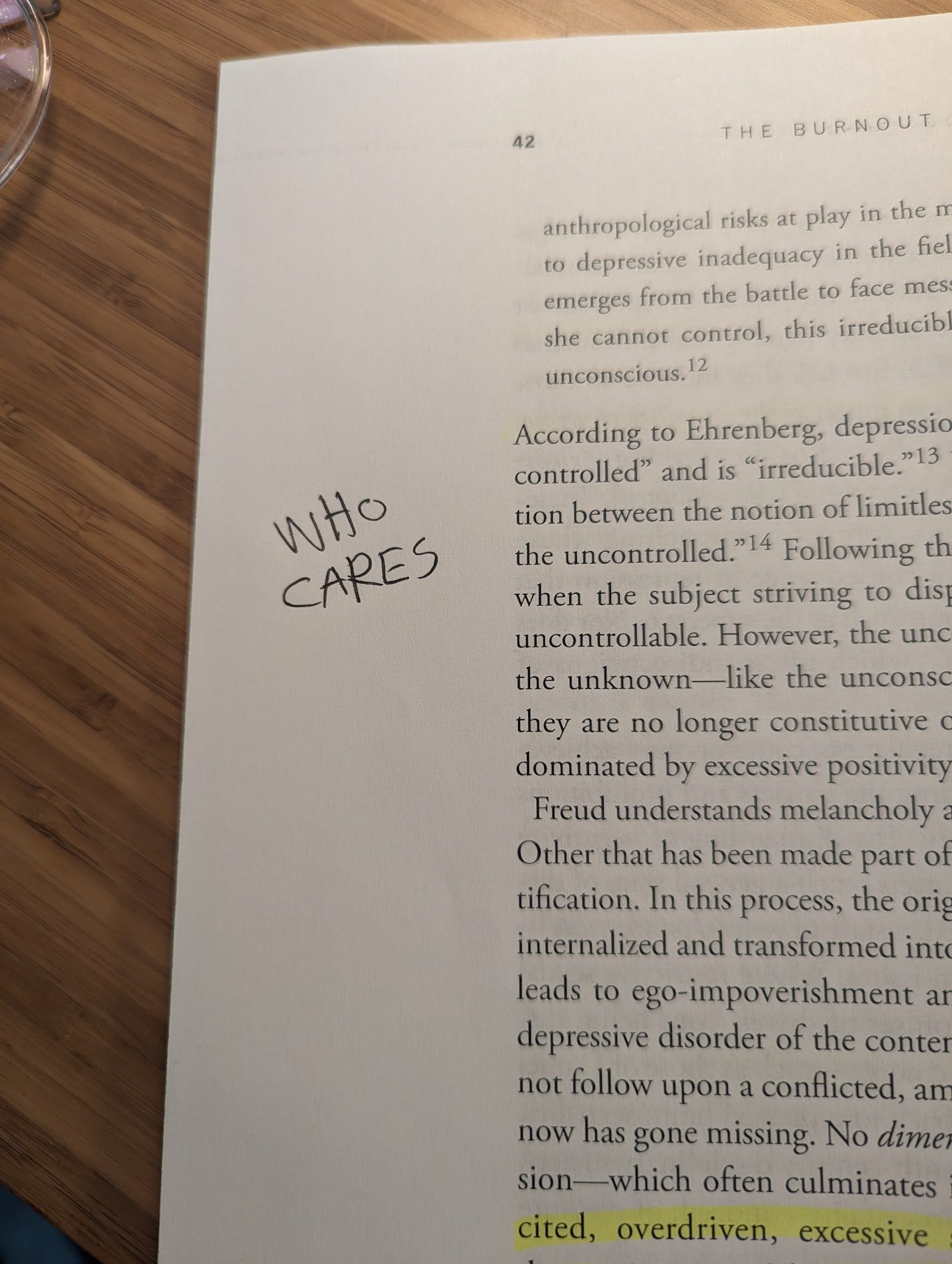

The Burnout Society isn’t long—just over fifty pages, excluding notes & citations—but it could have used some furthering editing. Han spends far too much time dunking on other academics for minor semantic differences between his anthropological framework and theirs. He’s compulsively polemical, in what felt like a status-seeking, dare I say achievement-hungry way. While reading a paragraph late in the text, in which Han lambasts another sociologist for associating depression with the psychoanalytic concept of the unconscious, I was obliged to write, purely for my own amusement, “WHO CARES”.

Still, as a person intimately familiar with burnout and depression, I did resonate with aspects of Han’s theory. I obviously fit the mold of the achievement-subject, whom he clearly pities. Han especially looks down on people who obsess about staying healthy (as I’ve been wont to do): “The mania for health emerges when life has become as flat as a coin and stripped of all narrative content, all value. […] Life reduced to bare, vital functioning is life to be kept healthy unconditionally. Health is the new goddess.” But outside my personal socioeconomic sphere, that is of the professional managerial class, I initially wasn’t sure how relevant or useful Han’s theory is. None of the characters in Help Wanted, with the exception of the two senior managers Big Will and Meredith, have much freedom to speak of. Most of them work two or three jobs, which I suppose is a sort of “auto-exploitation”, but it seems to be driven by necessity, rather than an “auto-aggressive” desire to out-compete themselves. They have to pay rent, medical bills, credit card debt; they are “disciplined” by the constraints of their economic situation.

But it’s the mere promise of economic mobility that does, in the end, transform the employees of Town Square into achievement-subjects. The plot of the novel hinges on this, when the store manager decides to leave for greener pastures. His impending departure creates the possibility that Meredith, the Movement Team manager, might take his place, which would allow Little Will, their group manager, to take her place, which would leave his position—salaried, with stable benefits—up for the taking. The rank and file members of Team Movement immediately organize themselves to try to rig Meredith’s ascension, giving each of them the greatest possible chance to secure that life-changing promotion.

Returning to Han’s theory, it’s unclear to me how he would advise the employees of Town Square to behave differently. He extols the virtues of boredom and contemplation, as a force to resist the pressures for constant action and achievement. This is, I think, solid advice for yuppies like me, who might otherwise waste their lives hunting for higher status and fatter paychecks. It doesn’t seem nearly as applicable for low-wage workers seeking basic stability, though. One vexing facet of modern capitalism that, for the individual, there can be tangible benefits to becoming your own slave driver.