This world devours every person and moves on. It does not stop moving, even as we pass through the middle of life telling ourselves it is the front end.

— “Your Real Biological Clock Is You’re Going to Die” by Tom Scocca

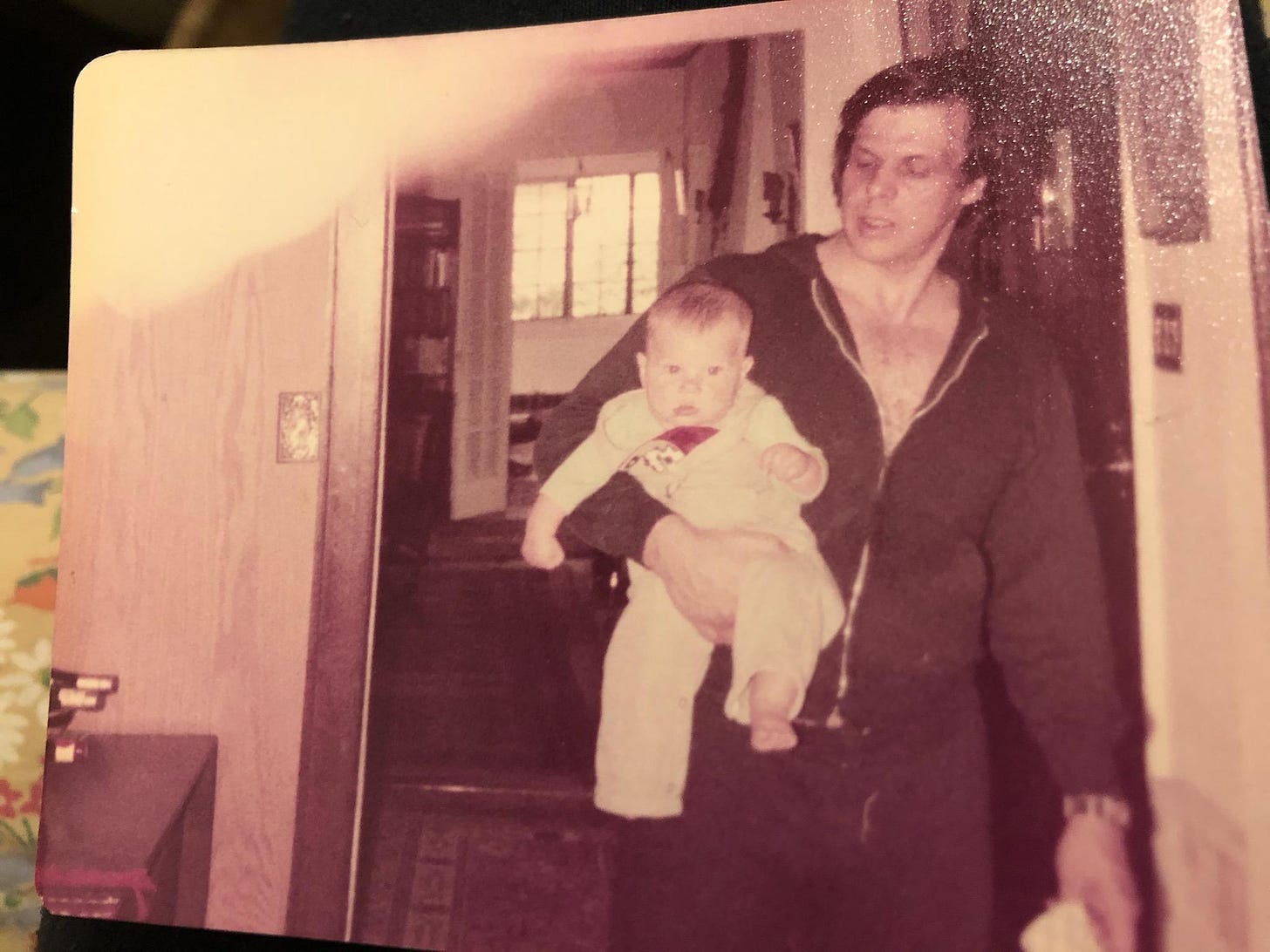

John (right) and Phil (baby)

John (right) and Phil (baby)

My uncle John died a couple weeks ago, on his 82nd birthday. I didn’t know him that well, even though we saw each other at least twice a year for all 30 years of my life, sharing a couch in my grandparents’ living room at Christmas or eating together at Thanksgiving. I want there to be a good reason for why we never formed a strong connection, but I think I was just too young and self absorbed to make a conscious effort to get to know him before his health deteriorated around ten years ago. After it had, I started to feel sheepish around him; I didn’t want to disturb his already-tenuous peace.

Now he’s gone, and I feel sad that I didn’t take advantage of the many, many chances I had to get to know him better. Could I have done any differently? Maybe, if I was a different, better person. But I wasn’t, and I didn’t.

John (right) & Helene (his daughter) at my parents’ wedding (left)

John (right) & Helene (his daughter) at my parents’ wedding (left)

Modern culture doesn’t provide us with very effective tools for dealing with death—neither the passing of friends and relatives, or our own eventual demise. Death, as an ever-present reality, the singular point towards which we are all slowly (or quickly) inching, is largely ignored, to the degree that it’s often considered impolite (or at the very least “quirky”) to discuss. Aging, meanwhile, we treat like a problem to be solved, with a healthy diet, exercise, and an ever-expanding array of obscure supplements & skincare products. There’s nothing wrong with trying to stay hot & healthy [I reapplied sunscreen in the middle of writing this paragraph], but we’ve become shockingly bad at preparing ourselves for the problem of death—a problem which, in all likelihood, cannot be solved.

In an attempt to more fully diagnose this issue, I came up with three broad categories to classify the attitudes toward mortality that I’ve witnessed amongst my cultural cohort:

- Self-imposed ignorance (“I just try not to think about it”).

- Denial; something to overcome (“Rage against the dying of the light”).

- Abject terror and/or depression (“Oh god, oh fuck, I’m going to die”).

I want to respond to each of these, and then talk about what I think might be a better approach.

Ignorance is bliss

Given that death & aging are a bit spooky, what’s so bad about just like… not thinking about them? Well, aging is happening and death is inevitable, whether or not you think about them. All of us will have to deal with them eventually, so we may as well prepare ourselves emotionally and physically for what is to come.

If you’re reading this in your 20s_,_ you’re most likely many years away from seriously feeling the ill effects of “getting old” (and like, same). You’ve probably got time to Hang Out and Vibe, and leave stressing about your cholesterol for another day. But, if you work a job with 401k matching, you’d be silly to not take advantage of that. Odds are you’ll someday be old enough to collect that free money, so why risk screwing over your future self?

It’s also worth considering the other people in your life—even if you yourself aren’t yet feeling the malignant effects of time’s passage, someone you love probably is. Your parents, your mentors, your older friends (if you have them)—there’s a diminishing window during which we share a time and place on earth. True even for folks your own age! You never know when someone will move away forever… or whatever else might happen to them. Better to cherish these fleeting moments, than ignore the fact that someday they’ll be gone.

Denial of death

Defeating death and halting aging has been the recurring dream of countless people across the millennia. From Gilgamesh to Qin Shi Huang, the quest for immortality is probably at least as ancient as the written word.

Lol. Lmao

Lol. Lmao

Today, this philosophy is best epitomized by Bryan Johnson (who’s long since left the 20-35 demographic, but he’s so mad about it), and the other Silicon Valley freakazoids taking experimental infusions of Literal Childrens’ Blood to extend their lifespans. [I know that sociologically this sucks ass, but can we also admit that it’s kinda metal?]

While I don’t think there’s anything inherently unethical about trying to avert death or slow aging, how you go about it makes all the difference. How many people are you willing to hurt, abuse, or neglect in your quest for immortality? What’s the opportunity cost [def] of pursuing everlasting youth? Is there some better way you could be spending your time, energy, and money? (Looking at you, Bryan.) Maybe you should spend your limited time on Earth doing something more fulfilling and useful, rather than trying to eke out a few extra years of hedonism.

Then there are those who would deny aging while accepting death, aspiring to “live fast, die young, and leave a beautiful corpse.” I’ve known several teens and twenty-somethings who claimed to live by this mantra, but I know fewer and fewer who still hope for an early death now that we’re nearing or entering our thirties. Still, I can’t judge people for wanting to avoid the question of aging, because, well…

Fear of death

Aging and death are not fun. No one would voluntarily give up the boundless energy or fast healing that came naturally to us when we’re young. Many folks my age are already starting to stiffen, our desk jobs (and desk hobbies) and irregular exercise habits catching up to us. For my older relatives, time seems to have stiffened too, their calendars calcifying around the many responsibilities of middle age. It makes perfect sense to be afraid of these changes.

Besides disability and death, you might also fear that you won’t accomplish the things you want to before some deadline. Many of these deadlines are self-imposed or arbitrary—you’re never really too old to publish a book, to go back to school, or to go solo traveling. But there are non-arbitrary deadlines too: the so-called “biological clock”, and more superficial (but no less real) deadlines like: Are you too old to become an olympic athlete? [Yes.] To climb Mt. Everest? [No, but I don’t want to.] Are you about to get kicked off of your parents’ health plan? [Fuck our healthcare system fr.]

Or perhaps we’re afraid to die without accomplishing as much as our heroes or peers, afraid that we won’t leave a proper “legacy”. I have less empathy for this perspective, as I simply don’t understand the legacy drive. In the grand scheme, no one will be remembered for very long. A year, a century, ten millennia, it’s all nothing compared to the grinding immensity of geologic time. Give it a couple million years and no one will remember Shakespeare or the pyramids, same as you and me.

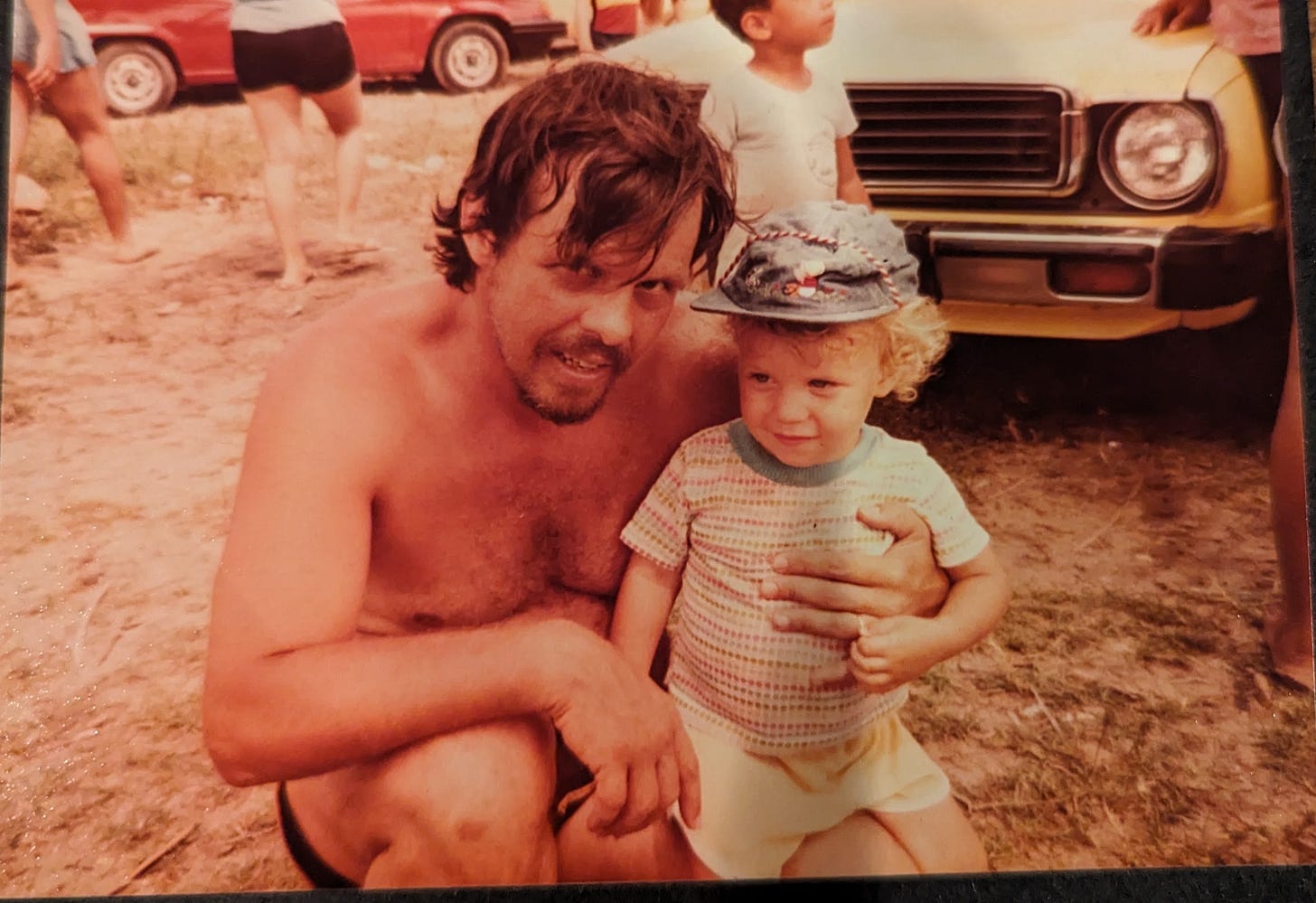

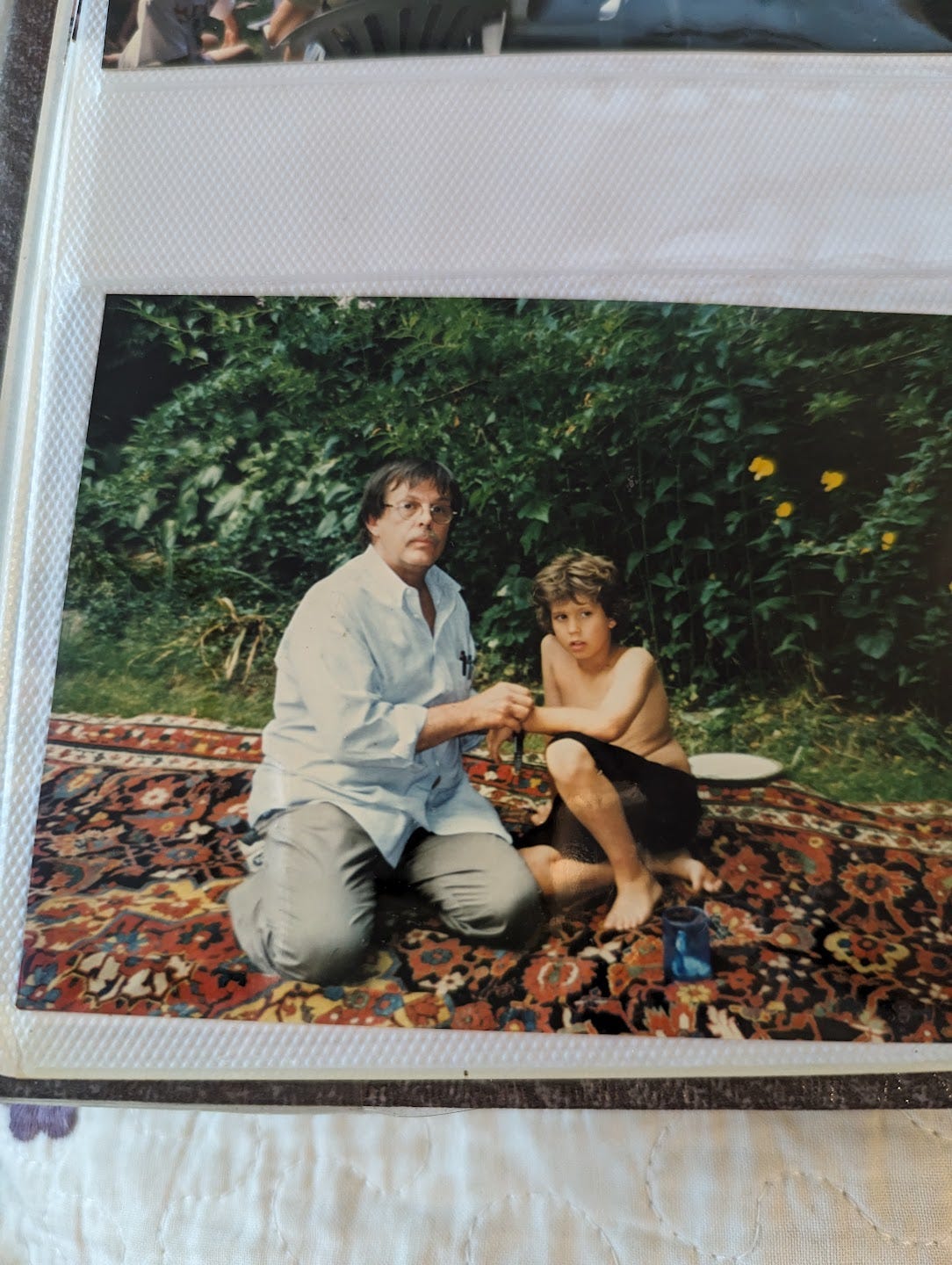

John & Phil (less baby)

John & Phil (less baby)

An alternative

So what do we do instead of stewing in our ignorance, denial, and/or fear? If at all possible, I think we should we should try to:

- Accept that we will age & die.1

- Live accordingly.

Finding acceptance

How do you accept your mortality? It depends on what how you’re wired, and what you’re receptive to. Religion works for some, but it didn’t do much for me (sorry mom & dad). Reading philosophy has helped, as well as lots of Sitting and Thinking and Talking with the smart, beautiful people in my life. Here are my main thoughts:

-

If death and aging are inevitable, what’s the use in worrying about them? As Kierkegaard wrote, “anxiety is the dizziness of freedom.” Short of suicide, I have no freedom to choose whether I’ll age, nor when I’ll die. I will definitely die, and if I’m lucky, I’ll get to age a bit first, so what’s the sense in being anxious about it?

-

Death is basically egalitarian, which as far as The Human Experience goes, is an uncommon property. With so much inequality and injustice in the world, I find it comforting to know that at the end of the day, we’ll all end up in the same place: super dead! Aging and disability, too, while unevenly distributed in duration and severity, will lay all of us low sooner or later. To quote Tom Scocca again, “the able and the disabled aren’t two different kinds of people but the same people at different times.”

I don’t want to give you the impression that I am “totally chill” with dying. I would actually love to stay alive, because I’m having a pretty good time of it all things considered. So, like most people, I take many steps every day to avoid dying. But, given that I will die, and that I am aging, I’d rather not waste time or effort stressing about those facts.

Live like you’re dying

So let’s say you’re working on accepting your aging and eventual death, or that you’ve achieved total acceptance and are well on your way to nirvana. Congrats! What do I mean by that second part, “live accordingly?” By this, I mean that we should all take death a bit more seriously when choosing how to conduct our day to day affairs. In other words: act like you’re going to die. It’s not quite as simple as “living every day like it’s your last”. That doesn’t work because, well, what if it ain’t your last? You still gotta pay your taxes, or it’s straight to tax jail. Oh no! [Oof, I really need to do my taxes.] What I actually mean is something much more subtle and mundane: that we should treat our lives, our loved ones, and our everyday experiences with the respect and reverence they deserve.

When I was younger, I spent far too many years “waiting for my life to begin”. Waiting to finish high school, to graduate college, to get a new job, to find the right city, or relationship. Waiting for something else to happen, besides what was already in front of me. Then, surely, once I reached that next step, I’d be able to start actually enjoying my life. But there was never a time when there weren’t endless things to learn, to appreciate, and enjoy. Sure, there were plenty of obstacles standing in the way of me having an Uncomplicated Good Time, the normal stressors of school, work, heartbreak, and injury.

But there was beauty too: music, and art, and books, and other people; friends, and family, and crushes, many of whom I’ll probably never speak to again. Our mortality makes our experiences rare, like precious gemstones. Every moment is worthy of appreciation, if we can only find the energy for it.

In The Anthropocene Reviewed, John Green writes about his encounter with a Cool Leaf:

Marveling at the perfection of that leaf, I was reminded that aesthetic beauty is as much about how and whether you look as what you see. From the quark to the supernova, the wonders do not cease. It is our attentiveness that is in short supply, our ability and willingness to do the work that awe requires.

Human beings are the same. There’s an infinite well of beauty that can be accessed and created through our relationships with other people, if only we can find the ability and willingness to do the work that love requires.

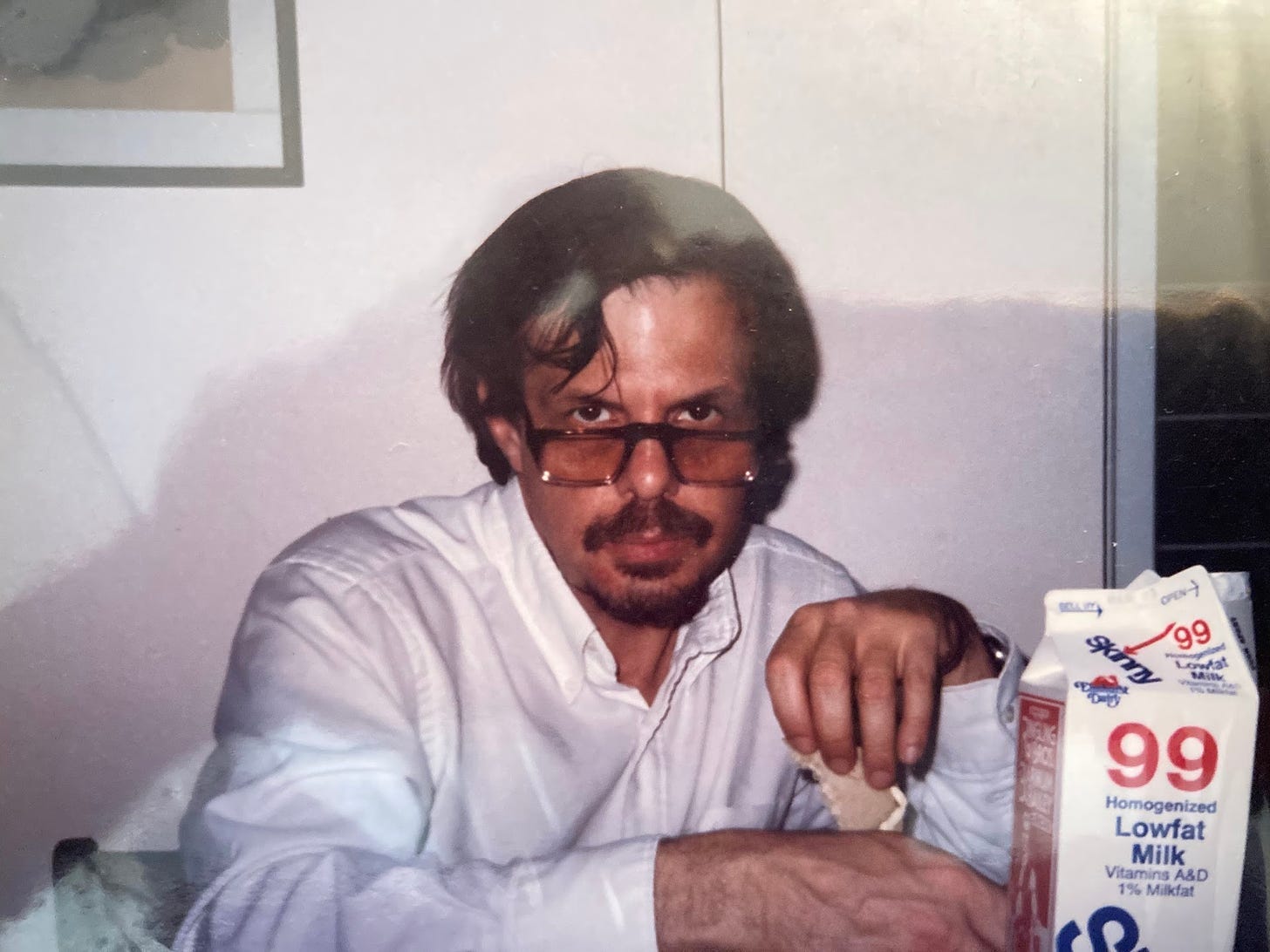

John & Joe

John & Joe

We had a memorial for John2 at my grandparents’ house, which I still think of as their house, even though they are both also dead now. I was sick with a cold, but my mom persuaded me to come anyway. I masked up and took the metro north, bumping into my cousin Lateef on the train platform. We sat in that same living room where my uncle and I had made so many faltering attempts at conversation over the years. My John’s kids shared stories about his life, while their kids, John’s grandchildren, eschewed any pretense of solemnity. They laughed and cried and screamed; one of them peed on the carpet. Soon they settled into a pattern of sprinting between the living & dining room, reemerging every so often with fistfuls of gooey, fresh-baked chocolate chip cookies.

Left to right: John, Phil, Helene, Ida, Peter

Left to right: John, Phil, Helene, Ida, Peter

I hope that whenever I happen to die, the people I love have some good stories to tell, and some delicious cookies to share. Here’s my favorite recipe if you need one.

John & Leo (Phil’s baby)

John & Leo (Phil’s baby)